Geospatial Data in 2026: How the Industry Has Evolved Since 2016

Ten years ago, geospatial data was mostly about maps, files and GIS tools. In 2026, it’s about data products, pipelines and real-time intelligence.

Location data now powers everything from climate modelling and insurance pricing to logistics optimisation and AI systems. But this didn’t happen overnight. The way geospatial data is collected, structured, managed and consumed has changed dramatically since 2016.

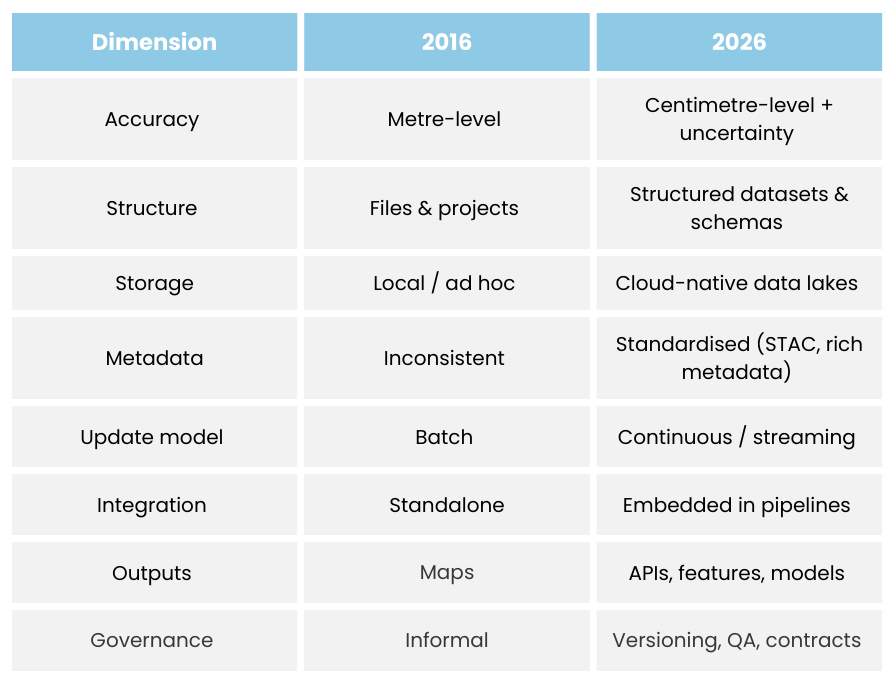

Here’s a practical breakdown of the key geospatial trends in 2016 compared with 2026.

Overview 2016 vs 2026

Geospatial Data in 2016: Where We Started

1. Positioning Data Was Good Enough for Humans, Not Machines

In 2016, most geospatial data came from everyday consumer devices such as smartphones, satnav systems and consumer-grade GPS units. Typical accuracy sat around 3–10 metres, which was perfectly adequate for navigation and basic mapping but limited the usefulness of location data for automation, advanced analytics or high-confidence decision-making. The European GNSS Agency noted that the majority of GNSS use at the time was still consumer-focused rather than industrial-grade. In practice, this meant organisations had limited trust in precision, datasets often lacked rich metadata, and there was very little information available about uncertainty or overall data quality.

2. Geospatial Data Lived in Files, Not Pipelines

Although “cloud GIS” platforms existed in 2016, most geospatial data was still handled in traditional ways. Data was typically uploaded manually, stored as static files, and organised by individual projects rather than treated as part of a wider data system. Common formats included shapefiles, GeoTIFFs and file geodatabases.

Metadata was inconsistent, automation was rare, and very few organisations treated geospatial data as a core component of their overall data architecture. Esri’s early discussions around cloud GIS reflect this transitional stage in the industry.

3. Big Geospatial Data Was More Hype Than Usability

The launch of the Copernicus Sentinel satellites significantly increased the availability of Earth observation data, with Sentinel-2 alone generating terabytes of data per day. However, despite the growing volume, many organisations struggled to extract real value from this data in 2016. Common challenges included discovering relevant datasets, accessing them efficiently, interpreting metadata, and combining data consistently over time.

There was no shortage of data, but there were relatively few genuinely usable geospatial data products that could be easily integrated into business workflows.

4. Drone Data Was High Quality but Isolated

Drone data was already proving valuable in 2016, particularly across sectors such as surveying, construction and agriculture. From a data perspective, however, it was usually collected for individual projects, processed manually, and delivered as static outputs such as orthomosaics or point clouds. It was rarely integrated with other datasets or treated as part of a broader data ecosystem. PwC’s drone report at the time highlighted the strong potential of the technology, but also pointed to limited integration at enterprise level:

5. Geospatial Data Management Was Mostly Manual

In many organisations, geospatial data management in 2016 was fragmented and highly manual. Analysts often owned their own datasets, files were stored on shared drives, and multiple duplicated copies of the same data were common. Version control was limited, automated validation was rare, and governance practices were generally weak. There was little alignment with emerging data engineering approaches, which meant geospatial data often sat outside mainstream data strategies. Gartner still primarily assessed vendors as GIS software providers rather than data infrastructure platforms, which reflected this broader industry mindset.

6. The Main Output of Geospatial Data Was a Map

For most organisations in 2016, the end result of geospatial workflows was usually a map, a dashboard or a report. Geospatial data was extremely effective for visual storytelling and communication, but it was rarely embedded into APIs, used directly in machine learning models, or integrated into core business systems.

Location data was primarily visual and descriptive rather than operational. It helped people understand what was happening, but it wasn’t yet driving automated decisions or powering critical systems.

Geospatial Data in 2026: Where We Are Now

Fast forward to 2026, and the shift is clear: geospatial is no longer about files and maps - it’s about data infrastructure.

1. Positioning Data Is Now High-Confidence and Continuous

Modern geospatial data pipelines increasingly rely on high-accuracy techniques such as RTK-enabled GNSS, multi-constellation signals (including GPS, Galileo, BeiDou and GLONASS), and sensor fusion that combines GNSS with IMU, computer vision and LiDAR. This shift means that datasets now commonly include centimetre-level accuracy, confidence scores, stronger temporal consistency and richer metadata about sensor provenance.

The UK government formally recognises Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) as critical national infrastructure, highlighting how important reliable location data has become. For data teams, this fundamentally changes how trustworthy and operational geospatial data can be.

2. Geospatial Data Is Designed for the Cloud, Not Just Stored There

In 2026, geospatial data is no longer simply uploaded to the cloud; it is designed for computation from the outset. Common patterns now include the use of object storage (such as S3, Azure Blob and Google Cloud Storage), cloud-optimised formats like Cloud Optimised GeoTIFFs (COGs), multi-dimensional array formats such as Zarr, and columnar formats like Parquet for structured spatial tables. Dataset catalogues increasingly follow the STAC specification, which has become a widely adopted way to make spatial datasets discoverable and machine-readable. At the same time, OGC APIs prioritise modern data access patterns over legacy map services.

The result is geospatial data that is queryable at scale, discoverable via APIs, easier to integrate with analytics platforms, and far more interoperable across systems.

3. The Focus Has Shifted from Raw Data to Data Products

One of the biggest geospatial trends in 2026 is the shift away from raw datasets towards high-value data products. Instead of simply delivering imagery, modern geospatial datasets increasingly provide derived outputs such as land use classifications, change detection layers, risk scores, probability surfaces, rich feature-level attributes and time-series indicators. The World Economic Forum describes this as a layered geospatial data ecosystem rather than a collection of raw feeds. McKinsey similarly frames geospatial as a data layer that feeds enterprise decision systems. This is where geospatial data starts to deliver clear, measurable business value rather than just technical capability.

4. Drone Data Is Becoming Continuous and Machine-Ready

Drone data in 2026 looks very different from what it did in 2016. Instead of being collected for individual projects and processed manually, it is increasingly captured on a continuous basis, automatically uploaded into data pipelines, enriched with metadata at source and validated using automated quality assurance processes.

At scale, drones are becoming part of ongoing spatial data infrastructure rather than one-off capture tools. Regulatory frameworks such as EASA’s U-space are actively enabling this shift towards more systematic and integrated drone data ecosystems.

5. Spatial Data Engineering Is Now a Real Discipline

Modern geospatial teams increasingly operate much like modern data teams. They focus on versioned datasets, automated validation, data contracts, reproducible pipelines, and observability and monitoring across their data workflows. Geospatial data now commonly lives within broader data architecture, including data lakes, spatial warehouses such as BigQuery GIS, Snowflake and PostGIS, feature stores for machine learning, and streaming pipelines for real-time use cases. CARTO’s concept of the Modern Spatial Data Stack captures this convergence between geospatial and data engineering particularly well.

6. The Real Output of Geospatial Data Is Now APIs, Models and Decisions

Maps still matter in 2026, but they are rarely the final output. Instead, geospatial data increasingly powers downstream systems such as risk scoring APIs for insurers, routing engines for logistics companies, site selection models for retailers, ESG and climate analytics platforms, and real-time operational dashboards. Digital twins are a strong example of this shift, as they depend on continuously updated, structured geospatial data rather than static 3D models. Deloitte similarly describes spatial data as an input layer for enterprise-scale decision systems.

This is what location intelligence looks like in practice - data that actively drives decisions, not just visualisations.

Geospatial Data Has Become a Core Data Asset

The evolution of geospatial data from 2016 to 2026 is not simply a story of better tools or nicer maps — it’s a shift in how organisations understand and value spatial data itself. What was once treated as specialist data owned by a small GIS team has become a foundational layer within modern data platforms, feeding analytics, automation and AI across the business.

The future of geospatial will belong not to those who simply visualise data, but to those who build strong, scalable and trusted spatial data foundations.

Discover more insights

Get the latest news, insights and trends from the GeoDirectory blog